In a predictive coding framework, which suggests that the brain continuously produce hypotheses that predict sensory input, anthropomorphism makes sense: when something looks like a human or moves or acts in a human-like way, it is more likely that your interaction with this agent will be efficient and smooth if you treat it as another human-being.

In fact, neuroscientific research has demonstrated that similar brain regions are activated when participants attribute mental states to non-human agents as when attributing mental states to other humans. Initially introduced to describe the appearance of religious agents and gods, the term is now used to describe human characteristics towards animals or plants, objects and technical devices, and even geometric shapes. Interestingly, humans spontaneously anthropomorphise non-human agents.

Second, through attributions that ascribe agency, affect, or intentionality to the non-human.

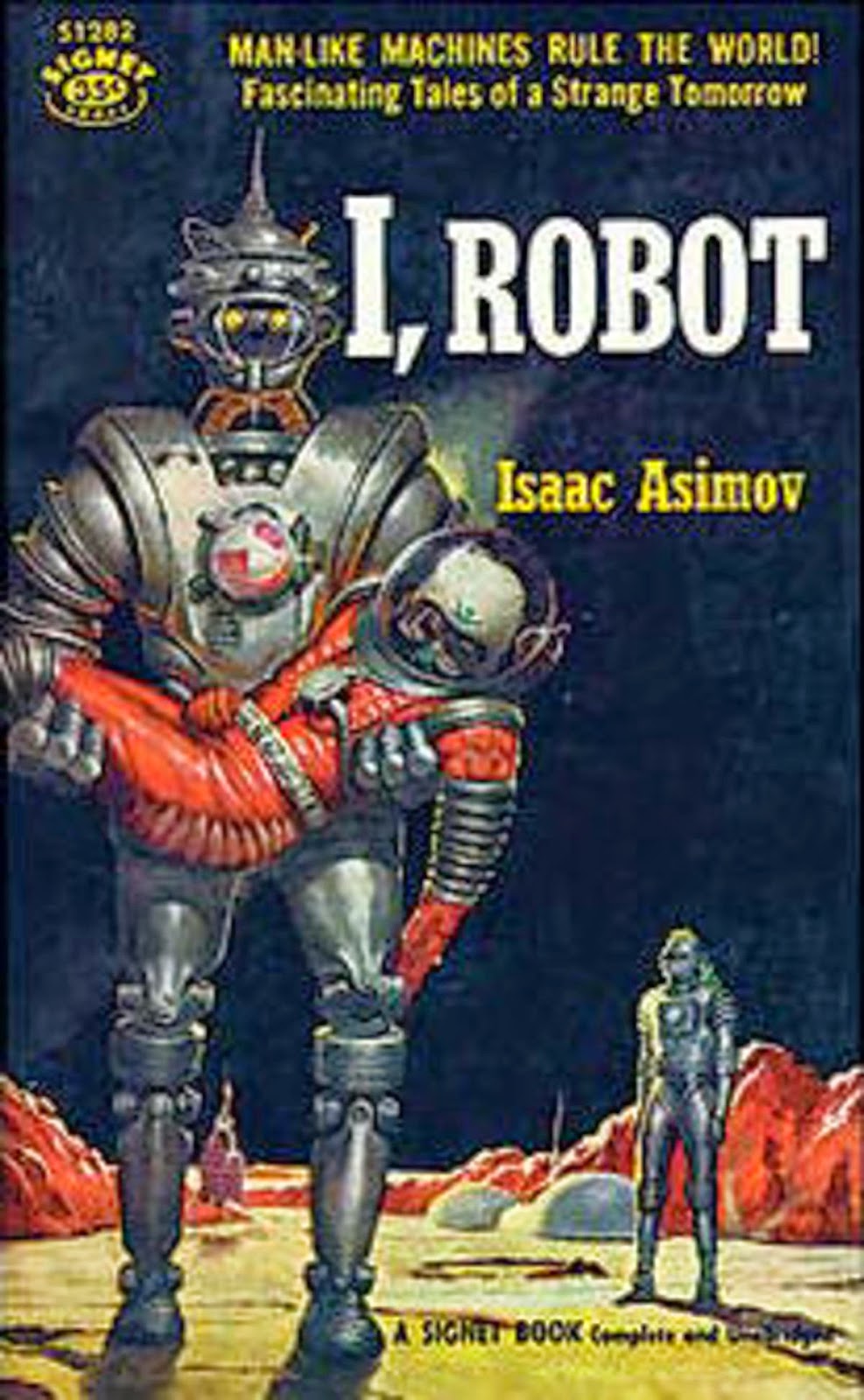

Anthropomorphism for non-human agents can be elicited in two ways: First, by increasing the physical appearance with humans. AnthropomorphismĪnthropomorphism involves “going beyond behavioral descriptions of imagined or observable actions (e.g., the dog is affectionate) to represent an agent’s mental or physical characteristics using humanlike descriptors (e.g., the dog loves me)”. In the present study, we investigated the factors that elicit these negative feelings and clarified possible underlying mechanisms, including the extent to which robots look human-like and the extent to which they are attributed with a mind. While, these technical developments are especially interesting when it comes to maintaining and improving our quality of life, for example in health care or education, a large body of research also shows that social robots tend to elicit negative feelings of eeriness, danger, and threat. Developments in robot technology are proceeding rapidly: ‘Social robots’, i.e., robots that are designed to interact and communicate with people, feature increasingly more human-like appearances and behaviour. Although highly evolved robots seem a vision of the future, we already interact with artificial intelligent agents on a regular basis (e.g., Siri, Apple’s speaking assistant, Amazon’s Alexa, or CaMeLi, an avatar designed to help elderly in daily life). Anthropomorphising Ava in this way, that is to ascribe human-like characteristics and/or intentions to non-human agents, is a fundamental human process that spontaneously happens and increases our social connection with non-human agents.

#WAS THE NUMBERLYS AN INFLUENCE FOR THE MOVIE ROBOTS ANDROID#

Watching the movie ‘ Ex Machina’, you quickly perceive Ava, the android main character of the movie, as a real human with emotions and feelings. Perceived agency and experience did not show similar mediating effects on human–machine distinctiveness, but a positive relation with perceived damage for humans and their identity. Replicating earlier research, human–machine distinctiveness mediated the influence of anthropomorphic appearance on the perceived damage for humans and their identity, and this mediation was due to anthropomorphic appearance of the robot. Participants were presented with pictures of mechanical, humanoid, and android robots, and physical anthropomorphism (Studies 1–3), attribution of mind perception of agency and experience (Studies 2 and 3), threat to human–machine distinctiveness, and damage to humans and their identity were assessed for all three robot types. In the present study, we explored whether and how human-like appearance and mind-attribution contribute to these negative feelings and clarified possible underlying mechanisms. However, a large body of research shows that these robots tend to elicit negative feelings of eeriness, danger, and threat. Social robots become increasingly human-like in appearance and behaviour.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)